|

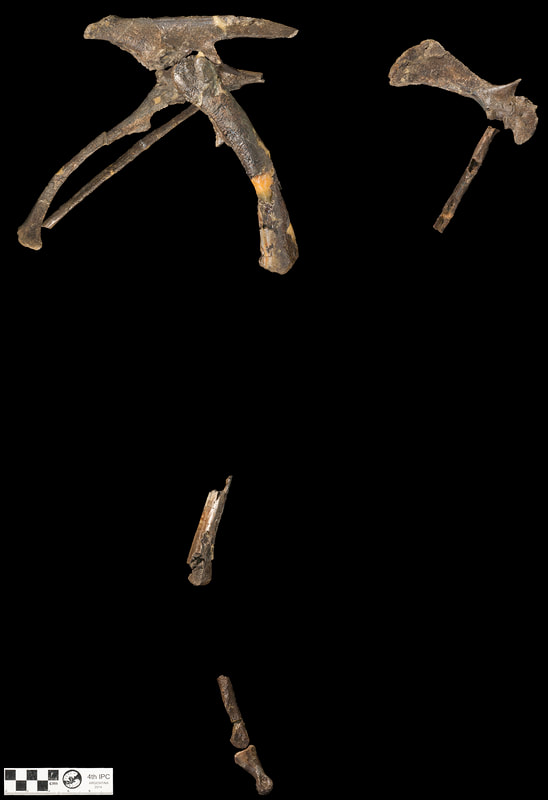

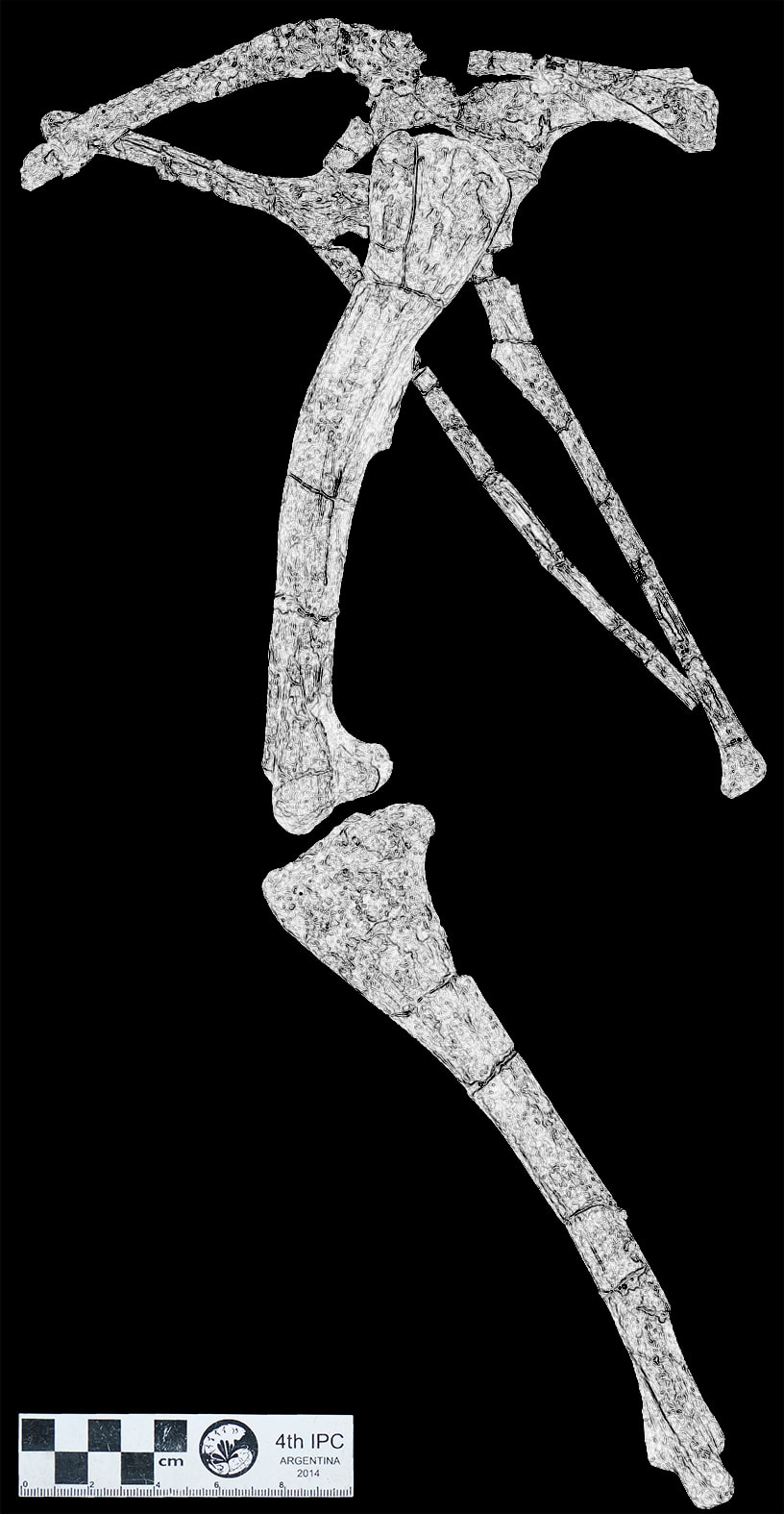

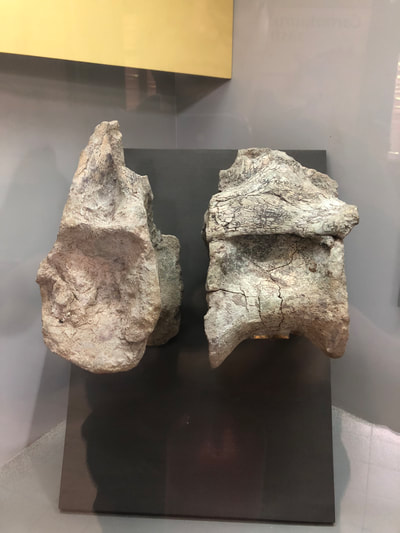

In previous posts, I have used a lot of superlatives to describe the quality of various specimens. Of those covered so far, Anabisetia and Macrogryphosaurus were the most spectacular among the ornithopods, and Megaraptor was awe-inspiring. I will be sure to utilise somewhat different superlatives to describe the dinosaur I worked on during my week in Trelew, and for the one I will be studying in my week in Río Gallegos. That said, I really should reserve some for the smallest dinosaur I have worked on so far, for it is one of historical significance in Argentinean palaeontology, and is represented by some absolutely wonderful specimens. The year was 1996. I was finishing high school. Non-hadrosaurid ornithopods from South America were effectively unknown. And then, with one publication in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado changed that. Although they provided scant details about how and when the fossils came to be found, or who collected the material, the specimens they described were amazing. The crown jewel was an almost complete skull, associated with an incomplete skeleton, of a dinosaur that was little bigger than a chicken. Coria and Salgado elected to name the new ornithopod Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, alluding to the place in which it was found (Cinco Saltos) with the species name, and honouring Zulma Gasparini, a world-renowned Argentinean palaeontologist, with the genus name. I have no doubt that she would have been absolutely chuffed to have such a magnificent specimen named after her, even though she mainly works on crocodiles and their kin, rather than dinosaurs Having now observed it for myself, I can say that the type skull of Gasparinisaura is absolutely exquisite. To be able to see the ridges and wear facets on the teeth and the holes that facilitated the passage of blood vessels into the jaw bones was simply phenomenal. I also realised that the palpebral — the bone above the eye socket that might have made these small ornithopods look perpetually angry — was broken. This was not evident from the published illustrations. The bones preserved with the skull were similarly spectacular, including the partial shoulder and pelvic girdles and even some complete limb bones. In their initial publication, Coria and Salgado mentioned only two specimens of Gasparinisaura, and almost all of the illustrations they provided (none of which were photographs) were based on the skeleton with the skull. The other specimen they reported, a partial tail, was only briefly summarised. However, the following year, Salgado, Coria and Susana Heredia reported the discovery of several new specimens of Gasparinisaura. They revealed that the locality from which the material was collected was situated 2.5 km southeast of the Cinco Saltos Cemetery — a juxtaposition of two graveyards of markedly disparate ages. In total, they reported twelve new Gasparinisaura specimens of varying levels of completeness: some comprised substantial portions of skeletons, others were only represented by one or two incomplete bones. Taken together, these specimens spanned quite a size range: from sub-chicken-sized individuals that were almost certainly juveniles to substantially larger exemplars. However, even the largest were still quite small by dinosaur standards! On one of the thigh bones of a particularly large individual, I observed a puncture mark that was clearly made prior to the bone being fossilised. This specimen was not illustrated by Salgado and colleagues, but they did briefly allude to it. Their conclusion as to the origin of the puncture seems perfectly reasonable to me: they interpreted it as a crocodylomorph tooth mark. This implied that this and other Gasparinisaura individuals might have fallen victim to an aquatic predator attack as they came down to drink at a waterhole. Whatever the crocs did not eat was eventually buried in sediment at the bottom of the water body and, ultimately, fossilised. Alternatively, the Gasparinisaura individuals might have been clustered around a drying waterhole, and later scavenged by opportunistic crocs who scattered their carcasses. With these new specimens available, the overall anatomy and appearance of Gasparinisaura became rather well understood. Some of the new specimens included portions of the tail, bones from the upper arm and forearm, partial pelves, articulated ankles, and even in two instances a fairly complete foot. However, many of the long bones (especially those of larger individuals) were incomplete: their top and/or bottom ends were often preserved, but their shafts were almost always missing. Unfortunately, this meant that gauging the relative proportions of the hind limbs was difficult. Amazingly enough, Gasparinisaura is now known from more than the 14 specimens described in the mid-1990s. In 2008, Ignacio Cerda announced the discovery of two new partial skeletons of Gasparinisaura. However, his interest in these specimens was not anatomical, even though they were quite complete (one of them includes a skull that has still never been described); instead, he reported the presence, in both new specimens and in the type specimen, of gastroliths: stomach stones! To find them associated with three specimens of the same species, in the same deposit, when no other rocks were found in the associated sediment, meant that their interpretation was unambiguous. Nevertheless, it seems strange that Gasparinisaura would need rocks to aid in digestion, because its teeth were clearly adapted for mastication. Perhaps, as a small dinosaur, it needed to be able to extract as much nutriment from its food as possible, and in order to achieve this it needed to pulverise whatever it was eating well beyond what its teeth were capable of. Cerda made a strong case for the interpretation of these rock clusters as gastroliths, even going so far as to demonstrate that the ratio between the mass of the stomach stones in a Gasparinisaura individual and its approximate mass was comparable to that found in modern birds. The most recent publication on Gasparinisaura was published in 2012 by Ignacio Cerda and Anusuya Chinsamy. In this work, they focused on the histology of Gasparinisaura: its internal bone structure. What they found, from their substantial sampling, was that Gasparinisaura grew and lived fast and — if the specimens known to date are anything to go by — often died young. Based on their observations, Gasparinisaura grew relatively rapidly until it reached ~60% of the size of the largest individual preserved. This growth did not always take place at a continuous rate, with some individuals showing evidence of brief periods of stasis. However, only after Gasparinisaura exceeded this size did growth slow down more dramatically: evidence of slower, periodically arrested growth was only seen in larger individuals. Nevertheless, it was clear that even the largest preserved individuals were still growing at their time of death. This suggested two possibilities: that Gasparinisaura’s growth was indeterminate — i.e. it never stopped growing until it died — or that no adult Gasparinisaura individuals were known. Cerda and Chinsamy suggested that the latter was more likely, and I agree. Overall, then, we have an amazingly clear picture of what Gasparinisaura looked like, how it grew, and of some aspects of its lifestyle. Having studied, photographed and measured all of the specimens I could lay my hands on, I can only say that it was an absolute delight. Studying the articulated specimen with gastroliths, in particular, was amazing. References Cerda, I.A., 2008. Gastroliths in an ornithopod dinosaur. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53, 351–355. Cerda, I.A. & Chinsamy, A., 2012. Biological implications of the bone microstructure of the Late Cretaceous ornithopod dinosaur Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32, 355–368. Coria, R.A. & Salgado, L., 1996. A basal iguanodontian (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous of South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16, 445–457. Salgado, L., Coria, R.A. & Heredia, S.E., 1997. New materials of Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis (Ornithischia, Ornithopoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina. Journal of Paleontology 71, 933–940.

5 Comments

While visiting Plaza Huincul a few weeks ago, I was chatting with Rodolfo Coria about my plans for the rest of my trip. When I mentioned that I was going to visit Lago Barreales to see ornithopods, he told me that one of the specimens — a dinosaur called Macrogryphosaurus — was so beautifully preserved that it was as if it had died yesterday. Intrigued, I could not wait to see it. I re-read the Macrogryphosaurus paper later that week, and found myself a little underwhelmed. The bones looked OK in the figures, but not earth-shatteringly awesome. I decided to reserve judgment until I saw the specimen for myself. Once my time in Plaza Huincul was up, I caught a taxi to Cipolletti. I had three days in the hotel to consolidate the work I had done to that point before Jorge Calvo, the palaeontologist at Lago Barreales, picked me up to take me there. Although the initial plan was to spend four days working there, I ended up doing so for seven days straight! I spent the first two on Megaraptor (as mentioned here) before moving on to Macrogryphosaurus, which I had finished with before the end of day four. Having now studied it firsthand, I could not agree more with Rodolfo — Macrogryphosaurus is amazing. The preservation of most of the bones is immaculate, despite the fact that many are broken and that the vertebrae between the hips have been slightly crushed. More amazingly, so much of the animal is preserved: most of the neck, the entire thorax, the whole pelvis and a significant portion of the tail. The ribs and several dorsal vertebrae have been left together, in the position in which they were fossilised, which made photographing them difficult. Nevertheless, I was quite happy with the results, despite the fact that I was not able to take any automatically stacked images, thanks to my computer/camera lens packing it in in Plaza Huincul! Backing up for a moment, I realise that I have not introduced Lago Barreales properly. The Museum known as Proyecto Dino sits on the north shore of Lago Barreales (Barreales Lake), about 88 km northwest of Neuquén. This lake, and its near neighbour Lago Marí Menuco, are artificial: once dry basins, a deliberate partial deviation of the Neuquén River has caused them to fill with water. As a result of numerous fossil discoveries in the area — particularly at a site now known as Futalognko — a research facility was built that now operates as a museum, an educational centre and a tourist attraction. In May 1999 — before the Proyecto Dino museum was built — the Universidad Nacional del Comahue ran a geological field trip to sites near Lago Marí Menuco. While there, the team was informed by a boy named Rafael Moyano of a dinosaur discovery. The specimen was collected and prepared, and in 2007 Jorge Calvo, Juan Porfiri and Fernando Novas described it as the new ornithopod species Macrogryphosaurus gondwanicus — the “Gondwanan big enigmatic lizard”. The specimen was found to be remarkable in several ways: bony plates were present on the rib cage that were only otherwise known from a few other ornithopods; the sternum had projections in three different directions; and the neck was quite long by ornithopod standards, comprising ten elongate vertebrae. As a result of studying Macrogryphosaurus, I now have an appreciation for just how weird it is compared to most other non-iguanodontian ornithopods. At around 5–6 metres long, Macrogryphosaurus was quite small as far as dinosaurs go, but relatively large for a non-iguanodontian ornithopod. Indeed, its only rival in that regard is another Argentinean ornithopod — which I’ll be studying in ten days’ time! Lastly, the neck of Macrogryphosaurus made me think of an east African antelope called a gerenuk. Gerenuks have much longer necks than other antelope, allowing them to browse at a higher level than would be possible for most other species. They also routinely rear up on to their hind legs so that they can reach even higher into the trees — up to two metres. Perhaps Macrogryphosaurus was putting its relatively long neck to a similar use? References Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D. & Novas, F.E., 2007. Discovery of a new ornithopod dinosaur from the Portezuelo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 65, 471–483. By the time I started high school, I had already wanted to be a palaeontologist for almost a decade. With the internet not really being a “thing” back then (at least not in my parents’ house), I lapped up any fossil stories that made the news; however, back then I was not in the habit of reading the newspaper much myself. Instead, I have my grandma to thank for helping me to keep abreast of the latest news. Every day she would read the newspaper from cover to cover, and if she found anything palaeontological, she would cut it out, write the date and the name of the paper on it, and give it to me whenever she next saw me. Although Grandma passed away more than fourteen years ago, I still have the books in which I glued all the clippings she gave me. I never intend to part ways with them — they are testament to the support she gave me in pursuing a palaeontological path, and I probably would not be anywhere near where I am now without her encouragement. So strong was the influence she had on me that I dedicated by Ph.D. to her memory. If I remember correctly, it was in one of the clipping that Grandma gave me, back in 1998, that I first found out about a new Argentinean theropod dinosaur. It had been given a very evocative name — Megaraptor, or “big plunderer” — and I could only imagine what it would have looked like as a living animal. The article even had an artist’s impression of the animal, which made it look like a scaled-up Deinonychus or Velociraptor. This was because, based on the bones at hand, Megaraptor had been interpreted as having a huge, sickle-like claw on its foot. Oh, how times have changed since then… From the top The type specimen of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii was collected from the Portezuelo Formation by a National Geographic Society-backed field crew, led by Fernando Novas. Novas named and described Megaraptor in a 1998 paper in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, and it is fair to say it sparked a media frenzy. The new theropod was not known from much material: an ulna (forearm bone), a manual phalanx (finger bone), an incomplete metatarsal (upper toe bone), and a claw. However, in terms of scale, the claw was practically off the charts: at almost 34 cm long, measured along the outer curve, it was gigantic. Novas compared the specimens with other theropod dinosaurs and determined that the claws on the second toes of dromaeosaurs and troodontids were most similar to that of Megaraptor. However, he also noted similarities between the ulna and those of more “primitive” theropods, and between the metatarsal and those of more “advanced” theropods called coelurosaurs. In the end, Novas conceded that robustly placing Megaraptor on the theropod family tree was not really possible based on the evidence at hand. As such, he classified it tentatively as a coelurosaur that had possibly converged with troodontids and dromaeosaurs by evolving an enlarged claw on its second toe. Our understanding of Megaraptor’s true nature did not advance until 2004, when Jorge Calvo and colleagues (including Novas) announced the discovery of a new specimen on the north shore of Lago Barreales. This Megaraptor was more complete than the original, preserving vertebrae from the neck and tail, parts of the shoulder and pelvis, a partial metatarsal and — amazingly — a complete forearm and hand. The latter was critical: a phalanx (finger bone) identical to that from the original Megaraptor specimen was present in the first finger, and right next to it was a huge, sickle-like claw, uncannily like the original! This showed, beyond any doubt, that the massive claw from original specimen did not belong to the foot at all, but was a hand claw. A slightly smaller, yet chunkier, claw was present on the second finger, and a relatively tiny claw tipped the third and final finger. Using both the original specimen and the new one, Calvo and colleagues attempted to work our Megaraptor’s position on the theropod family tree. Despite having the new specimen available, they still found it difficult to place it! They identified some features that Megaraptor shared with carcharodontosaurids (“shark-toothed lizards”), others more in line with far more basal theropods, and others that seemed to be convergent with spinosaurids. These authors ultimately concluded that Megaraptor was unique — that it represented a heretofore unknown group of theropods, characterised by massive, raptorial hands, that was probably not a part of Coelurosauria. It was to be another decade before a substantial advance in our understanding of Megaraptor itself was made. In 2007, two short papers specifically focused on Megaraptor were published by Juan Porfiri and colleagues: one suggested that it was gregarious (based on rather meagre evidence, in my mind), whereas the other attempted to determine its hunting mode and predatory adaptations based on the 2004 specimen. However, the more important advances to take place between 2004 and 2014 only partially involved Megaraptor itself: instead, the description of several new species, including the Australian Australovenator, allowed Megaraptor to be linked with other theropods around the world, and to the recognition (by Roger Benson and colleagues) of two new groups of theropods, one nested within the other. The less inclusive group was dubbed Megaraptora, and it included the eponymous Megaraptor along with Australovenator, the Japanese Fukuiraptor and the Argentinean Aerosteon and Orkoraptor. The more inclusive group, within which Megaraptora was nested, was termed Neovenatoridae, and allowed the British Neovenator and the Chinese Chilantaisaurus to join the party. The idea of a unified Megaraptora within Neovenatoridae was happily accepted by many scientists until 2013 when Fernando Novas and colleagues published a paper summarising the theropods from Patagonia. In it, they attempted to assess the relationships of Argentina’s carnivorous dinosaurs, and their analysis placed Megaraptor and its kin within Coelurosauria — as originally proposed by Novas in 1998. More bizarrely, however, Novas and colleagues suggested that megaraptorans were possibly closely related to tyrannosauroids. On the face of it, this would be very odd: advanced tyrannosauroids are characterised by having tiny arms tipped with small claws, in stark contrast to the huge arms and trenchant sickle-like claws of megaraptorans. Nevertheless, this idea was lent further support in 2014 when Juan Porfiri and colleagues described a juvenile Megaraptor specimen from the northern shore of Lago Barreales that seemed to show similarities to very “primitive” tyrannosauroids, i.e. those that had not yet taken on the typical huge head + tiny arms body plan of Tyrannosaurus and its close kin. My experience with Megaraptor, and megaraptorids The three key Megaraptor specimens — the type specimen, the referred specimen with a complete hand, and the juvenile — are held in three separate places within Neuquén Province, despite the fact that two of them are registered in the same collection. The original Megaraptor specimen is held in Plaza Huincul at Museo Carmen Funes (where Anabisetia and Argentinosaurus are also held), the specimen with complete hand is held at the Proyecto Dino Museum on the north shore of Lago Barreales, and the juvenile is held in the Earth Sciences Department at the Universidad Nacional de Comahue. Within a fortnight that was otherwise occupied with the study of ornithopods (and very few technological hiccups, thank goodness), I had seen and studied all three specimens — I spent half a day on the type specimen, almost two full days with the full hand and its associated material, and a rather tight four hours with the juvenile! I came away from this absolutely convinced that the original specimen and the one with a complete hand represented the same species, although I still have a few doubts about the juvenile (although I am convinced it is a megaraptoran: it is very similar to some other megaraptoran species). All three specimens were a joy to work with. The most exciting for me personally, though, was the one at Lago Barreales. Seeing every single bone in the hand, in exactly the right place, and being able to make fresh observations (and take photographs) of those specimens has helped me to understand just how variable the bones of the megaraptoran hand truly are, which will hopefully enable isolated finger bones to be identified correctly when they come to light. Having studied the remains of Australovenator wintonensis and now Megaraptor namunhuaiquii firsthand, I can attest to how similar they are to one another (with Australovenator being significantly smaller). I can also state that seeing these specimens has been exceedingly useful in my ongoing research on Victorian Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs — some new megaraptoran remains will hopefully be published on from Cape Otway quite soon, and this paper will be greatly enhanced now that I've seen so much of Megaraptor! References Benson, R.B.J., Carrano, M.T. & Brusatte, S.L., 2010. A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic. Naturwissenschaften 97, 71–78. Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D., Veralli, C.D.J. & Novas, F.E., 2002. Megaraptor namunhuaiquii (Novas, 1998), a new light about its phylogenetic relationships. I Congresso Latinoamericano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Octubre de 2002, Santiago de Chile, en calidad de Expositor. Calvo, J.O., Porfiri, J.D., Veralli, C., Novas, F. & Poblete, F., 2004. Phylogenetic status of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii Novas based on a new specimen from Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina. Ameghiniana 41, 565–575. Hocknull, S.A., White, M.A., Tischler, T.R., Cook, A.G., Calleja, N.D., Sloan, T. & Elliott, D.A., 2009. New mid-Cretaceous (latest Albian) dinosaurs from Winton, Queensland, Australia. PLOS One 4, e6190. Novas, F.E., 1998. Megaraptor namunhuaiquii, gen. et sp. nov., a large-clawed, Late Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18, 4–9. Novas, F.E., Agnolín, F.L., Ezcurra, M.D., Porfiri, J. & Canale, J.I., 2013. Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: the evidence from Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 45, 174–215. Porfiri, J.D., Calvo, J.O. & Dos Santos, D., 2007. Evidencia de gregarismo en Megaraptor namunhuaiquii (Theropoda, Tetanurae), Patagonia, Argentina. In 4th European Meeting on the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy of Latin America. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 8. Díaz-Martínez, E. & Rábano, I., eds, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Madrid, 323–326. Porfiri, J.D., Dos Santos, D. & Calvo, J.O., 2007. New information on Megaraptor namunhuaiquii (Theropoda: Tetanurae), Patagonia: considerations on palaeoecological aspects. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 65, 545–550. Porfiri, J.D., Novas, F.E., Calvo, J.O., Agnolin, F.L., Ezcurra, M.D. & Cerda, I.A., 2014. Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation. Cretaceous Research 51, 35–55. I was recently re-reading a few papers in anticipation of my visit to Lago Barreales, and it made me realise that almost all of Argentina’s non-hadrosaurid ornithopods have only come to light within the last quarter-century. The sole exception is Loncosaurus, which — as previously mentioned on this blog — masqueraded as a theropod for more than eighty years. Non-hadrosaurid ornithopods have been known from most other continents since the late 19th or early 20th centuries, although they remain entirely unknown from India and Madagascar. The first Argentinian non-hadrosaurid ornithopods (other than the non-diagnostic Loncosaurus) were announced in 1996, and since then five genera have been named. Two of these are based on single skeletons, one is based on an adult skeleton with remains of an infant, and the other two are based on multiple specimens. One of those based on multiple specimens is Anabisetia saldiviai, the bones of which are housed at the Museo Carmen Funes (MCF) in Plaza Huincul. The MCF is probably best known for housing the type specimen of Argentinosaurus huinculensis, one of the largest sauropods (and land animals) of all time. Unfortunately, when I visited the Museum proper it was closed for refurbishment. Nevertheless, curator Rodolfo Coria was kind enough to let me see the displays – and to spend a week behind the scenes! Few real fossils are on display at the MCF — Argentinosaurus being a notable exception. However, behind the scenes there were so many specimens, many of them holotypes, that it was hard to know where to begin and where to stop! While at the MCF, I worked most days from 10am to 7pm without a lunch break; a surprise asado on the Tuesday was, understandably, a welcome change. Nevertheless, I still barely managed to finish working on the specimens other than Anabisetia that I had gone to see (more on them later…) because I lost an entire day to camera trouble (a familiar theme on this trip, eh?). The computer program I had been using to take stacked images of fossils, DigiCamControl, inexplicably stopped talking to my macro camera lens, meaning that I had to resort to taking photos with narrow aperture and long exposure settings. The results were actually quite good, albeit somewhat less satisfactory than the stacked images. Glossing over what remains my most recent (and hopefully final) technological nightmare, the specimens of Anabisetia were absolutely amazing to work with. Most of the material is undistorted, much of it was found articulated, and at least four individuals are represented in the MCF collections. Of course, these fossils did not discover themselves: they were found by a farmer from Plaza Huincul. Does this sort of story sound familiar? Many dinosaur discoveries in Queensland are made by graziers, and the significance of the collection accrued by the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton since 1999 attests to the critical role that people living on the land play in enhancing our palaeontological understanding. The farmer who discovered the ornithopod remains that would become known as Anabisetia was Roberto Saldivia. Saldivia brought a few fossilised bone fragments to the MCF in 1993, where they were soon recognised as ornithopod remains. As a result of Saldivia’s discovery, the MCF mounted an expedition to Cerro Bayo Mesa (30 km south of Plaza Huincul), and — with Saldivia’s help — soon uncovered four partial ornithopod skeletons. Although the discovery was briefly mentioned in a 1996 abstract, almost a decade elapsed before the new ornithopod was officially named and described. A 2002 paper by Rodolfo Coria and Jorge Calvo finally announced Anabisetia saldiviai to the world. The genus name honours archaeologist Ana Biset, who helped to sort out provincial fossil legislation in Argentina, whereas the species name honours Saldivia for finding the first remains of Anabisetia. Although the original paper is fairly short and does not provide many measurements, it is quite well-illustrated but includes no specimen photographs. My mission at the MCF, then, was to measure and photograph as many Anabisetia specimens as I could, and to supplement the paper that described it with my own observations of those specimens. The bones comprising each specimen were stored in big wooden boxes, with the individual fossils supported in polystyrene trays. The sole exception was a complete hind foot, kept in the position in which it was found, which was kept in what looked like an upside-down fish tank sitting on a small trap door. Laid out on the table, they looked a little daunting! Nevertheless, I set to work, and over a period of three days I compiled a pretty comprehensive database on Anabisetia, so much so that I could just about write a complete osteology of the animal (with a little help…). One of the specimens even included a partial hand — with five fingers, One thing I did notice was that some of the “individuals” included elements that had to come from other animals. In one specimen, a complete left ilium (upper hip bone) was present, along with a second, incomplete left ilium; in another, three humeri (upper arm bones) were present. In each case, one specimen was preserved quite differently from the rest of the material registered with that specimen, so it seemed prudent to exclude it; however, it does mean that there are in fact more than four Anabisetia individuals known! When I thought about this a little more, I realised that Anabisetia is represented by as many partial skeletons as the whole of Ornithopoda in Victoria… we have to find more. While studying Anabisetia I realised that the proportions of its hind limbs were quite interesting. In my previous posts on Morrosaurus and Trinisaura, I scaled the missing parts of their tibiae (shinbones) using a Victorian ornithopod specimen known as ‘Junior’ (NMV P186047). Had I used Anabisetia instead, I would have reconstructed the shins of these animals as being much shorter: the shins of Anabisetia were only slightly longer than the thighs, whereas in ‘Junior’ the shins were about 40% longer than the thighs. This almost certainly reflects a behavioural disparity between ‘Junior’ and Anabisetia (in the parlance of some palaeos, ‘Junior’ was more cursorial), and it will be interesting to see whether the situation in other South American ornithopods is more in line with Anabisetia or ‘Junior’.

I also found it curious that one specimen of Anabisetia was represented by both femora (thighbones), but that these two bones looked completely different from one another despite being effectively identical in size and preservation. I consider the differences to be due to distortion either before or during the fossilisation process, and I think this will impact our understanding of ornithopod diversity in southeastern Australia where, on the basis of femora alone, it has been hypothesised that up to five different species were present. Lastly, I was intrigued to learn that all of the Anabisetia specimens had been found in close proximity to one another. Small-bodied ornithopods are often found clustered together: examples I can think of off the top of my head include the Dysalotosaurus bone bed at Tendaguru, the numerous Hypsilophodon specimens recovered from a small area on the Isle of Wight, and the specimens attributed to Leaellynasaura from Dinosaur Cove. It would be really interesting to find out why this is so. For now, though, I’ll leave it there: the next post will be on a quite different type of dinosaur… References Coria, R.A. & Calvo, J.O., 2002. A new iguanodontian ornithopod from Neuquen Basin, Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22, 503–509. It has been a while between posts; I can only apologise for that. Since I last posted, my phone died. Thankfully, though, that is the only new chapter in my technological horror story! On the plus side, since my last post I have also visited four museums/universities in three towns (Plaza Huincul, Cipolletti and Neuquén), as well as the Proyecto Dino Museum at Lago Barreales (where I could only get internet intermittently). I plan to visit one more museum while straddling Neuquén and Río Negro provinces (in Cinco Saltos) before departing for Trelew in Chubut Province on Friday. Between now and then, and also during the ~14 hour bus trip from Neuquén City to Trelew, I shall endeavour to summarise the past two-and-a-half weeks' work. First up, though, I will talk about the last of the dinosaurs I studied in La Plata: Antarctopelta oliveroi, the first (non-avian) dinosaur ever found in Antarctica. Before the 1980s, no Mesozoic dinosaur fossils had ever been found in Antarctica. Geological mapping and past fossil finds had demonstrated without doubt that Mesozoic rocks were present; however, to that point Mesozoic vertebrate fossils were only known from Lower Triassic rocks. This changed in January 1986, when Eduardo Olivero (Instituto Antartico Argentino) discovered a fragmentary — and rather severely permafrost-affected — dinosaur fossil in the Upper Cretaceous Santa Marta Formation on James Ross Island. By 1987, the specimen had been identified as an ankylosaur, and in July that year — at the 10th Brazilian Palaeontological Congress in Rio de Janeiro — its discovery was announced to the palaeontological community by Zulma Gasparini and colleagues. Its identity as an ankylosaur was well-established: the specimen included a partial jaw, teeth, vertebrae, and armour plates from the skull and body, all of which were extremely similar to other ankylosaurs known worldwide. However, the incompleteness of the specimen as a whole — and of each skeletal element recovered — made it difficult to determine where on the ankylosaur family tree the new form sat. Four years later, Olivero, Gasparini and colleagues summarised the research done to date on the ankylosaur, then discussed the implications of the dinosaur from an environmental and biogeographic perspective. The ankylosaur was found in a marine deposit. In layers both above and below that which produced the ankylosaur, the remains of marine reptiles had been identified, along with numerous marine invertebrate trace and body fossils. The discovery of both the ankylosaur and of fossil tree trunks and plant debris within the same rock formation suggests that land was not far away from this marine setting. As a consequence of this — and of known ankylosaur distribution at the time — Olivero and colleagues suggested that there was a continuous land bridge between South America and Antarctica during the Late Cretaceous. It was not until 1996 that a more complete description of the ankylosaur was published, by Zulma Gasparini and others, in the Proceedings of the Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium (Memoirs of the Queensland Museum). Despite the fact that these authors described several skeletal remains — teeth, vertebrae, portions of pectoral and pelvic girdle, and numerous armour plates — they did not name the ankylosaur, and even suggested that two individuals were present based on apparent size discrepancies between some of the bones. Based on features of the teeth they suggested that the ankylosaur was a nodosaurid, and based on differences between it and Kunbarrasaurus ieversi (then known as Minmi sp.) they suggested that these two southern ankylosaurs were not closely related. Instead, they suggested that the Antarctic ankylosaur was an encroacher from the north, and that it — like hadrosaurian ornithopods — had established itself in South America during the Late Cretaceous American interchange. Finally, in 2006, Leonardo Salgado and Zulma Gasparini named the Antarctic ankylosaur Antarctopelta oliveroi (“[Eduardo] Olivero’s southern shield”). These authors supplemented the description published by Gasparini and colleagues in 1996 by describing new material, redescribing old specimens and providing numerous illustrations of previously unfigured elements. They also determined that all of the specimens were size-congruent and most likely pertained to a single individual. Intriguingly, they also identified some features unique to Ankylosauridae, as well as many nodosaurid characteristics. Consequently, they were unable to work out exactly where Antarctopelta sat on the ankylosaur family tree, making its biogeographic significance unclear. Having now seen the specimen firsthand, I can sympathise with all of the authors that have worked on this specimen in the past: it is difficult to interpret. Many of the bones are incomplete, others are poorly preserved, and some are both! The vertebrae and toe bones are quite well-preserved but not particularly informative, whereas the armour is poorly preserved and most pieces are incomplete. CT scanning of the dentary would probably assist in determining the morphology of the unerupted teeth therein; that said, there are at least two very well-preserved teeth that have already yielded much information. Unfortunately, because of my camera troubles — and my dash to Buenos Aires from La Plata on what was my final day in the latter — I did not get to study Antarctopelta as thoroughly as I would have liked. However, I did identify one bone that appears never to have been described or mentioned: the coracoid! Even after ~70 million years, it still clicks on to the scapula to form the shoulder girdle of this Antarctic ankylosaur. More to come; since I last posted I have studied three specimens of Megaraptor and most of the fossils assigned to three South American ornithopod genera (Anabisetia, Macrogryphosaurus and Gasparinisaura). I have also seen some gigantic sauropods (Argentinosaurus, Futalognkosaurus), a few not so gigantic sauropods (Andesaurus, Limaysaurus, Pilmatueia), and so many other type specimens that I can barely believe it (just yesterday, for example, I saw Abelisaurus, Bonitasaura, Buitreraptor, Rocasaurus...). I haven't had the time to study them all, of course, but I've been taking as many happy snaps as possible and will try to get through them all in time! References De Ricqlès, A., Pereda Suberbiola, X., Gasparini, Z. & Olivero, E., 2001. Histology of dermal ossifications in an ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Antarctica. VII International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Buenos Aires, 30-6-2001: Asociacíon Paleontológica Argentina, Publicatión Especial 7, 171–174. Gasparini, Z., Olivero, E., Scasso, R. & Rinaldi, C., 1987. Un ankylosaurio (Reptilia, Ornithischia) Campaniano en el continente Antarctico. Anais do X Congresso Brasil de Paleontologia, Rio De Janeiro, 19–25 Julho, 1987, 131–141. Gasparini, Z., Pereda-Suberbiola, X. & Molnar, R.E., 1996. New data on the ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Antarctic Peninsula. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 39, 583–594. Olivero, E.B., Gasparini, Z., Rinaldi, C.A. & Scasso, R., 1991. First record of dinosaurs in Antarctica (Upper Cretaceous, James Ross Island): palaeogeographical implications. In Geological Evolution of Antarctica. Thomson, M.R.A., Crame, J.A. & Thomson, J.W., eds, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 617–622. Salgado, L. & Gasparini, Z., 2006. Reappraisal of an ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of James Ross Island (Antarctica). Geodiversitas 28, 119–135. Museo de La Plata is an amazing place. The building is monumental, the natural history displays are breathtaking and all-encompassing, and — based on my experience there over the past week — during opening hours, the place is packed! It is great to see so much interest in all aspects of natural history, let alone palaeontology, from the Argentinian public. Of course, I was only incidentally going through the display halls on my way to get lunch each day. Most of the time, I was in the basement, working on Antarctic dinosaurs in the collection. On Thursday morning, I finished working on one of them (leaving me with one-and-a-bit days to get through the other…), and it is that dinosaur I present to you today. In January 2008, geologists Juan Moly and Marcelo Reguero collected the fossilised skeleton of a small ornithopod in Santa Marta Cove on James Ross Island, Antarctica. At that time, the only ornithopod specimens reported from Antarctica were a partial skeleton of a medium-sized ornithopod that remains undescribed, and two isolated hadrosaur bones. The then new ornithopod was, and remains, the smallest ornithopod recovered from Antarctica, with an estimated overall length of 1.5 metres. Despite the effects of recent freeze-thaw cycles, a substantial portion of the skeleton was able to be recovered by Moly and Reguero. This then underwent preparation and conservation at Museo de La Plata, and by the early 2010s the specimen was ready for description. Rodolfo Coria lead authored the paper (with Moly and Reguero as coauthors), published in 2013, that officially named this Antarctic ornithopod Trinisaura santamartaensis. The “Trini” part of the genus name honours Trinidad Diaz, a geologist who did pioneering geological studies on the Antarctic Peninsula, whereas the species name alludes to Santa Marta Cove, where the specimen was discovered.  The right hind limb and forelimb of Trinisaura santamartaensis, viewed from the right hand side. The scaling of the limb bones was again based on the Victorian ornithopod specimen NMV P186047 ('Junior'), possibly referable to Leaellynasaura. The ilium (top bone in the pelvis) and scapula (shoulder blade) are both composites involving photographs of the left (flipped) and right elements superimposed. The "humerus" was the only bone that I was not sure about in terms of its identification; I wonder if it is in fact a metatarsal. The holotype and only known skeleton of Trinisaura includes several dorsal (thoracic), sacral (hip) and caudal (tail) vertebrae, both shoulder girdles, a bone identified as a humerus, four of the six bones in the pelvis (both ilia, and the right pubis and ischium), and several elements from the right hind leg and a few from the left one. Most are well preserved and undistorted (lefts and rights of the same bones show no difference in size or shape), but some were clearly more severely affected by weathering than others (like the femur). Altogether, then, we have a good understanding of the relative size and shape of Trinisaura. More importantly, it has proven possible to identify enough significant anatomical features in this specimen to differentiate it from other ornithopods and to assess its position on the ornithopod family tree. In their 2013 paper describing the new dinosaur, Rodolfo Coria and colleagues included Trinisaura in a phylogenetic analysis to determine its position among other ornithopods. They found that it sat on a branch among small- to medium-sized ornithopods from South America, including Gasparinisaura, Talenkauen and Anabisetia. Three years later, Sebastian Rozadilla and colleagues found that Trinisaura and these three ornithopods formed a natural evolutionary group together with Morrosaurus from Antarctica, and the Argentinian Macrogryphosaurus and Notohypsilophodon. In 2017, Daniel Madzia and colleagues found that the same group of ornithopods was more inclusive still, with the Australian Atlascopcosaurus and Qantassaurus joining the party. This ornithopod group, known as Elasmaria, was quite diverse during the Cretaceous in Gondwana based on the evidence at hand. The fact that the Antarctic Trinisaura and Morrosaurus, and ornithopods from Argentina and Australia, share several anatomical features and seem to be more closely related to one another than to ornithopods from elsewhere, suggests that there was a radiation of these plant-eating dinosaurs in the southern supercontinent Gondwana during the Cretaceous Period. Why this was so is unclear, although it might have been related to their geographic or climatic isolation from more northern ornithopod faunas. Indeed, despite the fact that the Cretaceous ornithopod record of Africa is poor, and that India and Madagascar have yielded none to date, it is interesting to note that one of the few known African taxa — Kangnasaurus coetzeei — also seems to show ties to this group. Hopefully, more fossils from the continents that formerly constituted Gondwana will be discovered and described in the near future to shed further light on this ornithopod radiation. References Case, J.A., Martin, J.E., Chaney, D.S., Reguero, M., Marenssi, S.A., Santillana, S.M. & Woodburne, M.O., 2000. The first duck-billed dinosaur (family Hadrosauridae) from Antarctica. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20, 612–614. Coria, R.A., Moly, J.J., Reguero, M., Santillana, S. & Marenssi, S., 2013. A new ornithopod (Dinosauria; Ornithischia) from Antarctica. Cretaceous Research 41, 186–193. Hooker, J.J., Milner, A.C. & Sequeira, S.E.K., 1991. An ornithopod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of West Antarctica. Antarctic Science 3, 331–332. Madzia, D., Boyd, C.A. & Mazuch, M., 2018. A basal ornithopod dinosaur from the Cenomanian of the Czech Republic. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, doi: 10.1080/14772019.2017.1371258. Rich, T.H., Vickers-Rich, P., Fernández, M. & Santillana, S., 1999. A probable hadrosaur from Seymour Island, Antarctica Peninsula. In Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium: National Science Museum Monograph, 15. Tomida, Y., Rich, T.H. & Vickers-Rich, P., eds, Tokyo, 219–222. Rozadilla, S., Agnolin, F.L., Novas, F.E., Aranciaga Rolando, A.M., Motta, M.J., Lirio, J.M. & Isasi, M.P., 2016. A new ornithopod (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica and its palaeobiogeographical implications. Cretaceous Research 57, 311–324. My first, and only previous, visit to La Plata was in 2013 during my first trip to Argentina. That trip was career-changing for many reasons, but it also taught me a few valuable lessons. On that first trip, I missed my first flight. I'd been in Queensland for several months (despite the fact that I was living and working in Sweden at the time) and forgot how chaotic Melbourne Monday mornings can be. I thought I'd left myself plenty of time to get to the airport by train and SkyBus... and I didn't. And because I missed that flight to Sydney, I missed the subsequent ones that would have taken me to Santiago and Buenos Aires. Pro tip: don't ever do this. Had I listened to Flight Centre, I would have had to pay more than the cost of a new set of flights to change them: thankfully, a kind gentleman from LAN Airlines was able to rectify the problem for about a third of what Flight Centre was going to charge me. I arrived in Buenos Aires a day late but made up for it by getting straight to work at Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales (MACN; 21th–24th August 2013). There I met with Paul Upchurch and Phil Mannion, with whom I'd be travelling for the rest of the trip (the vibe of this year's trip could not be more different; I'm travelling alone). We headed to La Plata on the 25th, and I had one good day in the collections (working mainly on Neuquensaurus) before my trip took a bit of a downward turn. I had had a dull earache for a week. I periodically moved my jaw and massaged behind my ear in order to ease the pain, but to no avail. After an interrupted sleep, during which I thought I had successfully unblocked my ear, I woke at 5:00am on the 27th to find that the entire left side of my face was paralysed. I was in shock. Could I have had a stroke? I checked my symptoms and they fit better with Bell's Palsy - my ear infection had become so severe and put my facial nerve under so much pressure that it stopped functioning! I immediately returned to Buenos Aires to see what could be done, and a doctor confirmed Dr Google's diagnosis and said that it should self-rectify. So, for the next two weeks, half of my face looked like Droopy Dog, but once we made it to Trelew I was back to "normal". Thus, my first trip to La Plata lasted a grand total of two nights rather than the projected four. Fast forward to October/November 2018, and La Plata struck again. However, just like last time, I can't really place the blame on the city itself. At the start of my last day at the MACN, my camera battery was running low. I inserted the battery into the charger, plugged it in to the powerboard I'd been using all week, and heard a "pop". Normally, a small orange light turns on when charging is in progress, but this no longer happened. Needless to say, I was a bit worried - my camera was essential to the success of the trip! Like an idiot, though, I put off trying to find a replacement charger (which, again, you should never do) until I got to - you guessed it - La Plata. Changing topic slightly for a moment: I made another mistake before arriving in La Plata. In May, I had sent Marcelo Reguero - the Collections Manager - an email requesting access to the two named Antarctic dinosaurs in the Museum's collection. At around the same time I was sending emails to curators and collections managers throughout Argentina and - much to my disdain - I received responses from no-one. I eventually realised that they were all going to my junk mail, and that their responses had been prompt; however, I somehow failed to notice that my request to study in La Plata had not been granted. I only realised my mistake the day before I was due to start researching! Frantically, the night before, I sent an email to Marcelo... and he agreed to let me study there for the whole week. Had the Museum been busier, or had those specimens been off limits for whatever reason, there would have been no reason for me to visit. Lucky! Another pro tip though: don't do this either! Back to my camera troubles: the charge in my batteries lasted until the end of my first day in La Plata. Once they were flat, I took action: the next morning, I went hunting for a universal charger, thinking that it would suit my purposes. I visited at least seven shops, showed them my camera's battery and asked them if they had anything that would work. None did. It started to rain, metaphorically and literally. Deflated, I headed towards the Museum and started typing notes about Antarctic dinosaurs while mulling over what to do. I eventually worked out that I could buy chargers online through Argentina's Amazon equivalent, MercadoLibre. With the help of Julia Desojo, I made the purchase and put the delivery address as the Museum itself. It was meant to arrive on Wednesday, but didn't. In the meantime, Julia let me use her camera (too kind), but I was still worried. By Thursday I'd all but given up - the charger had not arrived. Worse still, overnight I received an email from the courier company Ocasa that stated that they "could not find my address". How they could fail to find Museo de La Plata, one of the biggest and most prominent buildings in La Plata, beggared belief. With Marcelo's help, I contacted Ocasa, and was informed that I needed to pick up the package in person from a warehouse in Buenos Aires. It was 1.45pm on Friday; the warehouse closed at 6. I needed to get money out before departing (and was lucky to be able to do so - the bank wouldn't process the transaction, and I only arrived at the only official currency exchange building in La Plata at 2.45pm, about fifteen minutes before closing time). I left La Plata for Buenos Aires in a taxi (a trip which takes a little less than an hour, and costs the equivalent of ~70 AUD [more than I'd paid for the charger]), full of hope that I'd finally be able to get my charger and make the most of the rest of my trip. However, on arrival I was told that my package had been returned to the vendor. Without phone reception or wifi, I had no way of knowing who they were or getting in contact with them. Angry, frustrated and dismayed, I returned to La Plata. Once back, I used the Hotel's wifi to check my emails again. I found that the vendor had sent me an email with instructions for what to do if my package was undelivered. I noticed that the business was open from 11am-2pm on Saturdays, and that they had left a contact number. After trying (and failing) to talk with them in English, I was able to get one of the hotel attendants to call on my behalf - and found out that I could indeed pick up a charger in person the next day! I was elated... even more so when I picked up the charger this morning. In fact, as a failsafe I bought two; that caution has already been validated, since the light in one of them doesn't work even though it does seem to be charging the batteries. I'm now in Buenos Aires, heading to Plaza Huincul tomorrow. This evening, I will finish writing up the blog posts on the two Antarctic dinosaurs I studied in La Plata. If nothing else, this post will explain why my some of my specimen photos are not up to my usual standards! I would like to sign off by thanking Marcelo Reguero for hosting me at Museo de La Plata last week, and to Julia Desojo for being so helpful while I was there. I should also thank Martin Ezcurra for hosting me the week before last at the MACN. You guys are awesome - muchas gracias. Hi all — I am now in La Plata, and have been since Sunday. The only reason I have not posted anything from here yet is that I still have not finished studying either of the dinosaurs that are housed here that I wanted to see… That said, I do have something to show in the meantime. On my last day in Buenos Aires, it occurred to me that I had not gone through the displays at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales (MACN) properly. I failed to do so during my 2013 visit too, and I decided to remedy that this time. I would have taken far better photos than you will see here had I been able take my tripod in; sadly, I was not allowed. The dinosaur and reptile hall in the MACN is like a greatest hits album of Argentinian Mesozoic fossils — almost all of the classics are there. For the most part, I’ll let the photos (and captions) speak for themselves, and will hopefully report on an Antarctic dinosaur tomorrow!  Right hind limb of Morrosaurus antarcticus, viewed front-on. The scaling of the limb bones was based on the Australian ornithopod specimen NMV P186047 ('Junior'), which might be referable to Leaellynasaura. Right hind limb of Morrosaurus antarcticus, viewed front-on. The scaling of the limb bones was based on the Australian ornithopod specimen NMV P186047 ('Junior'), which might be referable to Leaellynasaura. Dinosaurs reign supreme in Antarctica today. Sounds weird, doesn't it? But it’s true! The reason? Every bird braving the frigid southern continent, be it a waddling penguin or a wandering albatross, is a living, breathing, highly derived theropod dinosaur. You might then wonder: Are the birds of modern day Antarctica continuing an ancient legacy? Did dinosaurs reign supreme in Antarctica during the Mesozoic Era? The answer to both questions, as has become clear in the last three decades or so, is emphatically yes. To date, Antarctica has only produced evidence of dinosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. All of the Jurassic specimens (of which I am aware) are held in institutions in the USA. However, fortunately for me, almost all of the Cretaceous-aged dinosaur specimens collected from Antarctica are housed here in Argentina. Next week, at Museo de La Plata, I will have the opportunity to study two of these. Earlier this week, however, I was privileged to be able to study the most recently named dinosaur from Antarctica — Morrosaurus antarcticus. In the last two blog posts, I was able to provide a fair bit of information about the collection history of the other dinosaurs I studied at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales — Loncosaurus argentinus and Chubutisaurus insignis. This was largely possible because such details were published as part of the papers in which these specimens were described. Frustratingly, a similar level of information was not easily available for Morrosaurus! All I found out is that it was collected by geologists Juan M. Lirio and Héctor Nuñez during 2002 (or perhaps a year or two prior), based on an abstract published in Ameghiniana by them — in conjunction with Fernando Novas and Andrea Cambiaso — that year. The type specimen of Morrosaurus (MACN 19777) comprises bits and pieces of a right hind leg. The shafts of the femur (thighbone) and the tibia and fibula (shinbones) are missing, but at least their top and bottom ends are preserved (only one end in the case of the fibula). By contrast, the metatarsals (the upper toe bones in the foot bound in flesh) are almost complete. In fact, I suspect that the only reason that they are incomplete is because of repeated freezing and thawing of the specimen: the part of Antarctica from which Morrosaurus derives is, in the modern day, covered by ice in winter but not summer. The metatarsals are quite distinctive: the middle one was evidently massive, whereas the flanking metatarsals are distinctly compressed, meaning that the metatarsus as a whole would have comprised a tightly-packed bundle of bones. Whether Morrosaurus possessed a rudimentary first and/or fifth toe is unknown based on the available material. The first description of MACN 19777 was produced by Andrea Cambiaso and included as part of her 2007 Ph.D. dissertation. However, Cambiaso never published on this specimen, and evidently did not consider it worthy of a name since she did not give it one. Finally, in 2016, Sebastian Rozadilla and colleagues (including Novas and Lirio) decided that it was worth naming MACN 19777, and they dubbed it Morrosaurus antarcticus. When I first saw the type specimen of Morrosaurus, I was struck by how large it was (well, relatively speaking; large for a small ornithopod, if you will). In fact, the same was true of Loncosaurus — both it and Morrosaurus were evidently quite a bit larger than even the largest of the known Cretaceous ornithopods from Victoria (Leaellynasaura, Atlascopcosaurus, Qantassaurus and Diluvicursor were quite titchy by comparison). Once I have seen Talenkauen and Macrogryphosaurus — both of which are larger still — I might ponder the significance of that size discrepancy further… for now though, I’ll press on. Morrosaurus lived during the Maastrichtian stage (72–66 Ma), the last phase of the Cretaceous Period. At that time, Antarctica was in much the same position on the planet as it is today, but both Australia and South America were situated further south and at least intermittently connected to Antarctica. Critically, Earth as a whole was far warmer than it is today, so much so that even the southernmost continent was evidently ice-free all year round — at least as far as the geological record tells us. Instead, it was covered in forest, and was clearly quite suitable for dinosaurs — remains of ornithopods, ankylosaurs, sauropods and theropods (including birds) have all been found in the López de Bertodano Formation, the rock unit from which Morrosaurus derives. Specifically, Morrosaurus itself was found at a locality called “The Naze”, more properly known as Península el Morro (from which its name derives), on James Ross Island. Finally, it should be noted that Morrosaurus is not the only ornithopod dinosaur to have been found in Antarctica, nor was it the first to be discovered there. That honour goes to a presently undescribed ornithopod, held in the United Kingdom, which was first reported on in 1991 but remains undescribed. The only other ornithopod specimens from Antarctica are a few hadrosaur fragments, and another small ornithopod — which is one of the two Antarctic dinosaurs I shall see at La Plata next week! More on both of them then. References Barrett, P., Milner, A. & Hooker, J., 2014. A new ornithopod dinosaur from the latest Cretaceous of the Antarctic Peninsula. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts of Papers, Seventy-fourth Annual Meeting 34, 85A–86A. Cambiaso, A.V., 2007. Los ornitópodos e iguanodontes basales (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) del Cretácico de Argentina y Antártida. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 410 pp. (unpublished). Case, J.A., Martin, J.E., Chaney, D.S., Reguero, M., Marenssi, S.A., Santillana, S.M. & Woodburne, M.O., 2000. The first duck-billed dinosaur (family Hadrosauridae) from Antarctica. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20, 612–614. Hooker, J.J., Milner, A.C. & Sequeira, S.E.K., 1991. An ornithopod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of West Antarctica. Antarctic Science 3, 331–332. Novas, F. E., Cambiaso, A. V., Lirio, J. M., & Nuñez, H. J. (2002). Paleobiogeografía de los dinosaurios polares de Gondwana. Ameghiniana, 39, 15R. Rich, T.H., Vickers-Rich, P., Fernández, M. & Santillana, S., 1999. A probable hadrosaur from Seymour Island, Antarctica Peninsula. In Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium: National Science Museum Monograph, 15. Tomida, Y., Rich, T.H. & Vickers-Rich, P., eds, Tokyo, 219–222. Rozadilla, S., Agnolin, F.L., Novas, F.E., Aranciaga Rolando, A.M., Motta, M.J., Lirio, J.M. & Isasi, M.P., 2016. A new ornithopod (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica and its palaeobiogeographical implications. Cretaceous Research 57, 311–324. Argentina was home to huge diversity of long- (and even some short-) necked sauropods during the Cretaceous Period (145–66 Ma). Indeed, the first dinosaurs named and described from Argentina were all sauropods — I might write more on them next week, since many of those specimens are housed at Museo de La Plata; that said, while there I have bigger (albeit literally smaller) fish to fry... It is fair to say that the true abundance and diversity of sauropods in the Argentinian Cretaceous has only really been revealed in the last thirty years or so, with the late Jaime Powell’s 1986 Ph.D. thesis (published in full in 2003) catalysing much of the subsequent research on titanosaurs in particular. Nevertheless, some very important Argentinian sauropods were named before Powell’s monumental manuscript, and one of these was Chubutisaurus insignis. Starting in February 1965, agronomical engineer Julio Fernández Duque and palaeontologist Guillermo del Corro spent 30 days excavating fossilised dinosaur bones from a site near Cerro Barcino and Cerro Winches in Chubut Province. The bones, which were first discovered by a local rancher named Mr Martínez (whose widow had informed Duque of their existence), were preserved in such hard rock that Duque and del Corro had to use dynamite in order to extract them. A substantial quantity of fossil material was recovered from the site, and all of the bones appeared to belong to a single sauropod dinosaur — except for five theropod teeth, which were named Megalosaurus inexpectatus by del Corro in 1966. All of these bones were deposited in the collections of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales in Buenos Aires, with the exception of two fragmentary limb bones that were donated to the Museo Provincial de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanografía in the 1970s. Ten years after the excavations took place, del Corro described and named the sauropod from Chubut as Chubutisaurus insignis (the “notable Chubut lizard”), which he classified in its own family, Chubutisauridae. However, del Corro illustrated only a small subset of the available material and misinterpreted several specimens. He also suggested that Chubutisaurus was Late Cretaceous in age, but provided little evidence to support this interpretation. His paper — preliminary by his own admission — would need to be followed up by a more comprehensive work down the line. In 1978, José Bonaparte and Zulma Gasparini highlighted the fact that Chubutisaurus was more “primitive” anatomically than the titanosaurs that were so characteristic of South America during the Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma). Consequently, they suggested that Chubutisaurus was actually substantially older than suspected by del Corro; based on microfossils from the same formation that had been interpreted as Aptian in age (125–113 Ma), they suggested Chubutisaurus was actually from the Early Cretaceous. Twelve years later, in the Sauropoda chapter of The Dinosauria, John McIntosh illustrated several of Chubutisaurus’ limb bones and suggested that it was a brachiosaurid. However, it was not until 1993 that a more comprehensive, albeit still abbreviate, description was published by Leonardo Salgado. He suggested against classifying Chubutisaurus as a brachiosaurid, because he considered the anatomical features that McIntosh had used to link the two as shared “primitive” characters. However, Salgado did identify some features that could be used to link brachiosaurids, Chubutisaurus and titanosaurs, indicating a possible relationship between all three. In 1991, a few years before Salgado’s paper on Chubutisaurus was published, the Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio (MPEF) launched a field trip to try to relocate Duque and Del Corro’s quarry. They were able to do so with the help of Mr Martínez’s son, who had been present when Duque and del Corro excavated the site in 1965. In 1991, and in 2007 as well, the MPEF team collected more material of Chubutisaurus — some of which had been transported some distance from their original positions by the force of the 1965 dynamite blasts. All of the material collected by the MPEF came to reside in the Museum in Trelew, meaning that the only known specimen of Chubutisaurus is now divided between three separate museums! A complete description of Chubutisaurus was only published relatively recently (2011) by José Carballido, Diego Pol, Ignacio Cerda and Leonardo Salgado. These authors concluded that Chubutisaurus was of Cenomanian age (~100.5–93.9 Ma) and that it was more closely related to titanosaurs than to brachiosaurs. Indeed, in both their analysis and in most recent analyses of sauropod interrelationships, Chubutisaurus is resolved as a basal somphospondylan — a close relative of titanosaurs, but not a true titanosaur itself. The material on which Chubutisaurus is based — which derives from the Bayo Overo Member of the Cerro Barcino Formation, Chubut Province — is extremely incomplete, although in fairness that is not a rarity for sauropods. The few thoracic vertebrae preserved suggest that those situated near the front of the chest — and therefore at the base of the neck — were quite short front-to-back but tall top-to-bottom. Further back in the sequence, the inverse holds true. Although no neck vertebrae were found, it can be inferred that the neck was quite long — partly because Chubutisaurus was a sauropod, for which long necks were the norm, but also because the short vertebrae at the front of the thorax were probably so short front-to-back (relatively speaking) to cope with the stresses imposed upon them by the movements of a long neck. By contrast, the tail of Chubutisaurus — although nowhere near complete — was presumably shorter than the neck: all of the tail vertebrae known are (again, relatively) short front-to-back. The tail vertebrae of Chubutisaurus are interesting for another reason: they are not procoelous. The centra (vertebral bodies) of procoelous vertebrae are concave on the front articular face and convex on the back one. However, those of Chubutisaurus are shallowly concave on the front face but essentially flat on the back face. This easily distinguishes the tail vertebrae of Chubutisaurus from those of most titanosaurs, the sauropods for which Argentina has become famous, because almost all of them have procoelous tail vertebrae; only in the most basal titanosaurs are the tail vertebrae not procoelous (as in the Australian Savannasaurus) or only incipiently so (as in the basalmost titanosaur by definition, Andesaurus). That'll do for now; once I have had a look at the girdle and limb bones of Chubutisaurus, I might have more to say... in the immediate future, however, I need to move on to another dinosaur — one from the southernmost continent of all! References Bonaparte, J.F. & Gasparini, Z.B., 1978. Los sauropodós de los Grupos Neuquén y Chubut, y sus relaciones cronológicas. Actas del VII Congreso Geológico Argentino, Neuquén, 1978 2, 393–406. Carballido, J.L., Pol, D., Cerda, I. & Salgado, L., 2011. The osteology of Chubutisaurus insignis Del Corro, 1975 (Dinosauria: Neosauropoda) from the ‘Middle’ Cretaceous of Central Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31, 93–110. Del Corro, G., 1966. Un nuevo dinosaurio carnívoro del Chubut (Argentina). Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales (Bernardino Rivadavia), Communicaciones Paleontología 1, 1–4. Del Corro, G., 1975. Un nuevo saurópodo del Cretácico Superior, Chubutisaurus insignis gen. et sp. nov. (Saurischia, Chubutisauridae nov.) del Cretácico Superior (Chubutiano), Chubut, Argentina. Actas I Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Biostratigrafía, 229–240. McIntosh, J.S., 1990. Sauropoda. In The Dinosauria. Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H., eds, University of California Press, Berkeley, 345–401. Powell, J.E., 1986. Revisión de los titanosauridos de América del Sur. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina, 472 pp. (unpublished). Powell, J.E., 2003. Revision of South American titanosaurid dinosaurs: palaeobiological, palaeobiogeographical and phylogenetic aspects. Records of the Queen Victoria Museum 111, 1–173. |

Stephen PoropatChurchill Fellow (2017) on a palaeo-tour of Argentina! Archives

December 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed