|

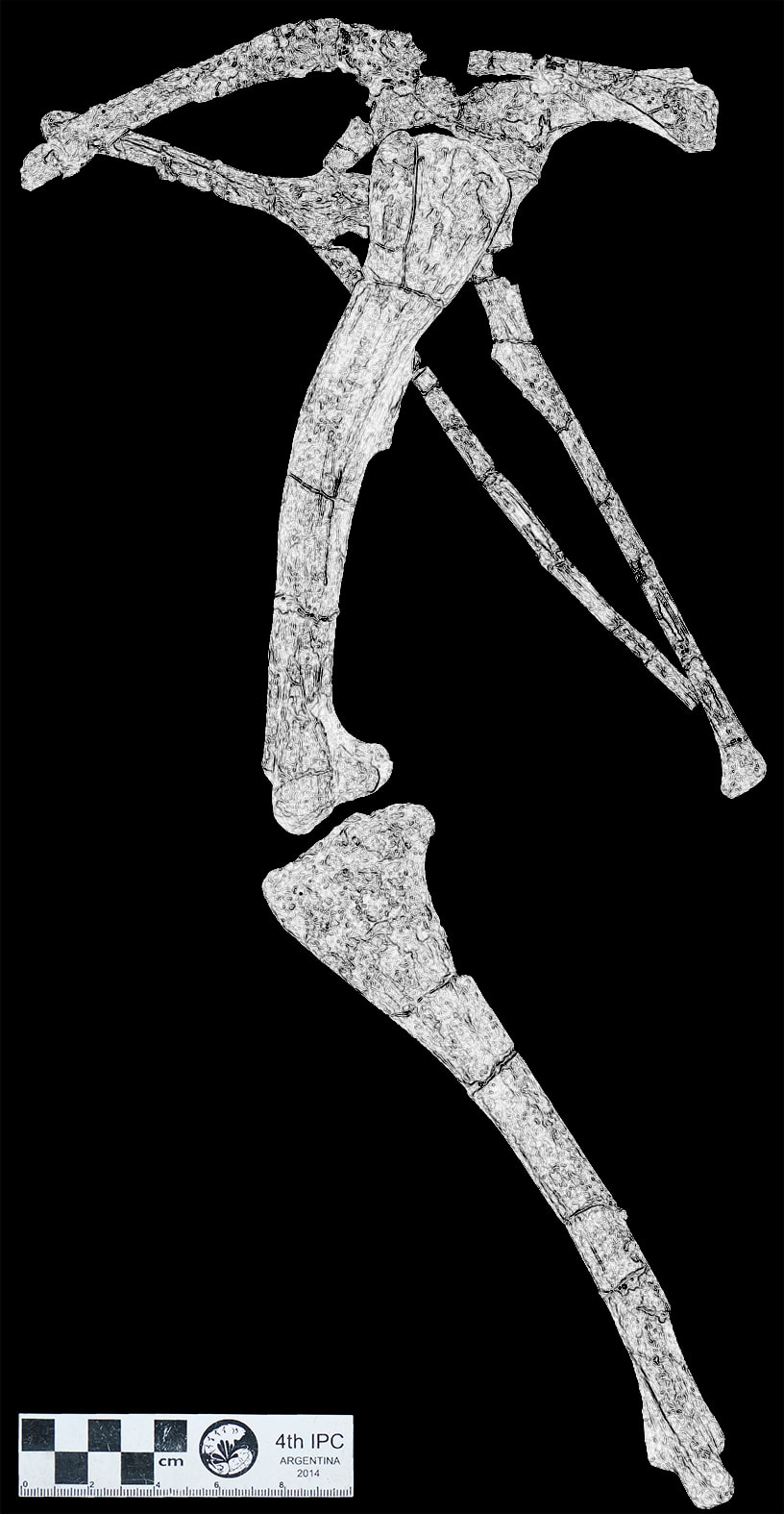

I was recently re-reading a few papers in anticipation of my visit to Lago Barreales, and it made me realise that almost all of Argentina’s non-hadrosaurid ornithopods have only come to light within the last quarter-century. The sole exception is Loncosaurus, which — as previously mentioned on this blog — masqueraded as a theropod for more than eighty years. Non-hadrosaurid ornithopods have been known from most other continents since the late 19th or early 20th centuries, although they remain entirely unknown from India and Madagascar. The first Argentinian non-hadrosaurid ornithopods (other than the non-diagnostic Loncosaurus) were announced in 1996, and since then five genera have been named. Two of these are based on single skeletons, one is based on an adult skeleton with remains of an infant, and the other two are based on multiple specimens. One of those based on multiple specimens is Anabisetia saldiviai, the bones of which are housed at the Museo Carmen Funes (MCF) in Plaza Huincul. The MCF is probably best known for housing the type specimen of Argentinosaurus huinculensis, one of the largest sauropods (and land animals) of all time. Unfortunately, when I visited the Museum proper it was closed for refurbishment. Nevertheless, curator Rodolfo Coria was kind enough to let me see the displays – and to spend a week behind the scenes! Few real fossils are on display at the MCF — Argentinosaurus being a notable exception. However, behind the scenes there were so many specimens, many of them holotypes, that it was hard to know where to begin and where to stop! While at the MCF, I worked most days from 10am to 7pm without a lunch break; a surprise asado on the Tuesday was, understandably, a welcome change. Nevertheless, I still barely managed to finish working on the specimens other than Anabisetia that I had gone to see (more on them later…) because I lost an entire day to camera trouble (a familiar theme on this trip, eh?). The computer program I had been using to take stacked images of fossils, DigiCamControl, inexplicably stopped talking to my macro camera lens, meaning that I had to resort to taking photos with narrow aperture and long exposure settings. The results were actually quite good, albeit somewhat less satisfactory than the stacked images. Glossing over what remains my most recent (and hopefully final) technological nightmare, the specimens of Anabisetia were absolutely amazing to work with. Most of the material is undistorted, much of it was found articulated, and at least four individuals are represented in the MCF collections. Of course, these fossils did not discover themselves: they were found by a farmer from Plaza Huincul. Does this sort of story sound familiar? Many dinosaur discoveries in Queensland are made by graziers, and the significance of the collection accrued by the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton since 1999 attests to the critical role that people living on the land play in enhancing our palaeontological understanding. The farmer who discovered the ornithopod remains that would become known as Anabisetia was Roberto Saldivia. Saldivia brought a few fossilised bone fragments to the MCF in 1993, where they were soon recognised as ornithopod remains. As a result of Saldivia’s discovery, the MCF mounted an expedition to Cerro Bayo Mesa (30 km south of Plaza Huincul), and — with Saldivia’s help — soon uncovered four partial ornithopod skeletons. Although the discovery was briefly mentioned in a 1996 abstract, almost a decade elapsed before the new ornithopod was officially named and described. A 2002 paper by Rodolfo Coria and Jorge Calvo finally announced Anabisetia saldiviai to the world. The genus name honours archaeologist Ana Biset, who helped to sort out provincial fossil legislation in Argentina, whereas the species name honours Saldivia for finding the first remains of Anabisetia. Although the original paper is fairly short and does not provide many measurements, it is quite well-illustrated but includes no specimen photographs. My mission at the MCF, then, was to measure and photograph as many Anabisetia specimens as I could, and to supplement the paper that described it with my own observations of those specimens. The bones comprising each specimen were stored in big wooden boxes, with the individual fossils supported in polystyrene trays. The sole exception was a complete hind foot, kept in the position in which it was found, which was kept in what looked like an upside-down fish tank sitting on a small trap door. Laid out on the table, they looked a little daunting! Nevertheless, I set to work, and over a period of three days I compiled a pretty comprehensive database on Anabisetia, so much so that I could just about write a complete osteology of the animal (with a little help…). One of the specimens even included a partial hand — with five fingers, One thing I did notice was that some of the “individuals” included elements that had to come from other animals. In one specimen, a complete left ilium (upper hip bone) was present, along with a second, incomplete left ilium; in another, three humeri (upper arm bones) were present. In each case, one specimen was preserved quite differently from the rest of the material registered with that specimen, so it seemed prudent to exclude it; however, it does mean that there are in fact more than four Anabisetia individuals known! When I thought about this a little more, I realised that Anabisetia is represented by as many partial skeletons as the whole of Ornithopoda in Victoria… we have to find more. While studying Anabisetia I realised that the proportions of its hind limbs were quite interesting. In my previous posts on Morrosaurus and Trinisaura, I scaled the missing parts of their tibiae (shinbones) using a Victorian ornithopod specimen known as ‘Junior’ (NMV P186047). Had I used Anabisetia instead, I would have reconstructed the shins of these animals as being much shorter: the shins of Anabisetia were only slightly longer than the thighs, whereas in ‘Junior’ the shins were about 40% longer than the thighs. This almost certainly reflects a behavioural disparity between ‘Junior’ and Anabisetia (in the parlance of some palaeos, ‘Junior’ was more cursorial), and it will be interesting to see whether the situation in other South American ornithopods is more in line with Anabisetia or ‘Junior’.

I also found it curious that one specimen of Anabisetia was represented by both femora (thighbones), but that these two bones looked completely different from one another despite being effectively identical in size and preservation. I consider the differences to be due to distortion either before or during the fossilisation process, and I think this will impact our understanding of ornithopod diversity in southeastern Australia where, on the basis of femora alone, it has been hypothesised that up to five different species were present. Lastly, I was intrigued to learn that all of the Anabisetia specimens had been found in close proximity to one another. Small-bodied ornithopods are often found clustered together: examples I can think of off the top of my head include the Dysalotosaurus bone bed at Tendaguru, the numerous Hypsilophodon specimens recovered from a small area on the Isle of Wight, and the specimens attributed to Leaellynasaura from Dinosaur Cove. It would be really interesting to find out why this is so. For now, though, I’ll leave it there: the next post will be on a quite different type of dinosaur… References Coria, R.A. & Calvo, J.O., 2002. A new iguanodontian ornithopod from Neuquen Basin, Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22, 503–509.

1 Comment

Solicitar un préstamo ahora

1/23/2024 10:40:51 am

Buenos días señor / señora,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Stephen PoropatChurchill Fellow (2017) on a palaeo-tour of Argentina! Archives

December 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed